Kenya ordered closure of Dadaab refugee camp this year, according to leaked UN document

Kenya has ordered the closure of the

Dadaab refugee camp by the middle of this year with the race now on to find

homes for more than 210,000 people, according to a leaked internal United

Nations document obtained by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Citing "national security

concerns", the Kenyan government wrote to the United Nations refugee

agency (UNHCR) on Feb. 12 about plans to close Dadaab within six months and

asking the agency "to expedite relocation of the refugees and asylum-seekers

residing therein". Officials from Kenya's interior ministry did not

immediately respond to requests for comment, but the UNHCR confirmed the plan.

"UNHCR is aware of the renewed

call by the Government of Kenya to close Dadaab and is working with the

government to continue to implement long-term and sustainable solutions for

over 210,000 refugees living in the camp," said the UNHCR in a statement

emailed to the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"These include voluntary returns, third

country solutions such as resettlement, sponsorships, family reunifications and

labour migration, as well as relocations in Kenya, including at Kakuma refugee

camp and Kalobeyei Settlement."

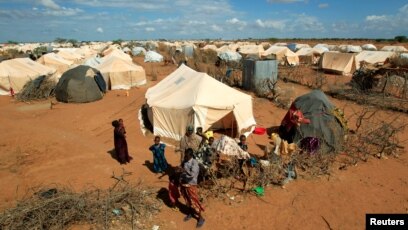

Located in eastern Kenya, Dadaab was

established almost 30 years ago and was once the world's largest refugee camp,

at its peak providing shelter to about half a million people who were fleeing

violence and drought in neighbouring Somalia.

Kenyan authorities announced plans in 2016 to

shut Dadaab, citing concerns that Somalia-based al Shabaab militants were using

it as a base to plan attacks in Kenya. But

the High Court blocked the move in 2017, saying it was unconstitutional and

violated Kenya's international obligations.

Human rights groups criticised the

renewed push to close Dadaab, saying it threatened the rights and safety of the

mostly Somali refugees, who could be forced to return home.

"The authorities should ensure

that any refugee returns are voluntary, humane, and based on reliable

information about the security situation in Somalia," said Otsieno

Namwaya, Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch (HRW).

"Forcing them to go back to face

violence or persecution would be inhumane and a violation of Kenya's legal

obligations."

HRW said although the specific reasons for

the renewed demand to close Dadaab were not clear, Somali refugees were often

blamed by Kenyan government officials for terrorist attacks in the country,

although no evidence has been provided.

According to the U.N. document, UNHCR has

helped almost 83,000 people return to Somalia voluntarily since 2015. But the

number of returnees dropped last year to about 7,500 compared to about 35,500

in 2017 and 34,000 in 2016.

As Somalia descended into civil war,

Dadaab was established by the United Nations in 1991, and has since mushroomed,

with more refugees streaming in, uprooted by drought and famine as well as

on-going insecurity. Many have lived there for years.

The settlement, spread over 30 square km

(7,415 acres) of semi-arid desert land, has schools, hospitals, markets, police

stations, graveyards and a bus station.

Kenyan government restrictions mean refugees

cannot leave the camp to seek work so people have few ways to earn a living

other than rearing goats, manual labour and running kiosks and rely on food

rations, much of these sent by foreign donors.

Source: Thomson Reuters Foundation

Comments

Post a Comment